Estimated Tax Payments Are Not Just for the Self-Employed

Ensure you're not caught off guard by tax obligations: Even those with income from sources like investments or partnerships, subject to no withholding, may need to make estimated tax payments to avoid penalties, a process often misunderstood but crucial for financial planning.

Unlike employees, who have income, Social Security, and Medicare taxes withheld from their wages, self-employed individuals must prepay their taxes by making periodic estimated tax payments. These are referred to as estimated tax payments because the self-employed individual must estimate his or her net earnings for the year and pay taxes per an IRS schedule according to that estimate. Failure to do so will result in interest penalties.

The self-employed are not the only ones who are subject to estimated tax payment requirements; anyone who has income on which no income tax has been withheld, and even those whose taxes are not sufficiently withheld, should be making estimated tax payments. Thus, if you have income from stock sales, property sales, investments, taxable alimony, partnerships, S-corporations, inherited pension plans, or other sources that are not subject to withholding, you may also be required to pay either estimated taxes or an underpayment penalty. Others subject to making estimated payments are individuals who must pay special taxes such as the 3.8% tax on net investment income or the employment tax on household employees.

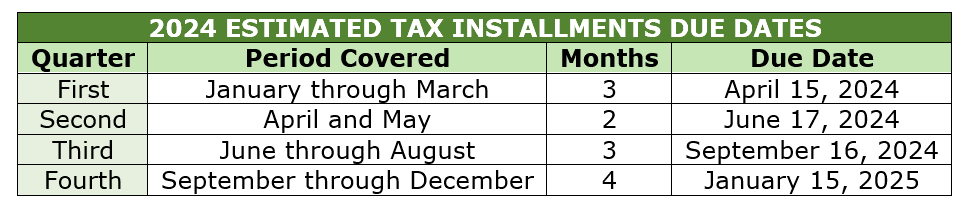

Although these payments are often termed “quarterly” estimates, the periods they cover do not usually coincide with a calendar quarter.

An underestimate penalty does not apply if the tax due on a return (after withholding and refundable credits) is less than $1,000; this is the “de minimis amount due” exception. When the tax due is $1,000 or more, underpayment penalties are assessed.

These underpayment penalties are determined per the periods as shown in the above table, so an underpayment in an earlier period cannot be made up for in a later period; however, an overpayment in an earlier period is applied to the following period.

The amount of an estimated payment is determined by estimating one fourth of the taxpayer’s tax for the entire year; the projected tax is paid in four installments. When the income is seasonal, sporadic, or the result of a windfall, the IRS provides a special form, and the underpayment penalty is based on actual income for the period.

For individuals who do not want to take the time to estimate their tax for the current year but who still want to avoid the underpayment penalty, Uncle Sam also provides safe-harbor estimates. However, even these can be tricky. Generally, a taxpayer can avoid an underpayment penalty if his or her withholding and estimated payments are equal to or greater than

• 90% of the current year’s tax liability or

• 100% of the prior year’s tax liability.

However, these safe harbors do not apply if the prior year’s adjusted gross income is over $150,000, in which case, the safe harbors are

• 90% of the current year’s tax liability or

• 110% of the prior year’s tax liability.

Sometimes, individuals who have withholding on some (but not all) of their sources of income will increase that withholding to compensate for the additional income sources that have no withholding. Although this may work, withholding adjustments are not as precise as the per-period payments and should be used with caution.

This office can assist you in estimating payments, adjusting withholding, and setting up safe-harbor payments. Please call for assistance.